Dear (Future) Designer: Accessibility Is Not A Feature

Design for everyone, not just the average user

Dear (Future) Designer,

At some point in your career, you will hear this sentence:

We will add accessibility later.

It usually sounds reasonable. The deadline is close. The scope is full. The design already works for most users. Accessibility becomes a task parked somewhere between polish and cleanup.

This is where things quietly go wrong.

Accessibility is not something you add on top of a finished design. It is not a toggle. It is not a checklist you complete at the end. Accessibility is a quality of the design itself.

Imagine designing a building with stairs everywhere, then adding a ramp as an afterthought. Technically, you made it accessible. Practically, you told some people they were not part of the original plan.

Digital products work the same way.

Color contrast, text size, focus order, keyboard navigation, readable labels, and clear hierarchy are not edge cases. They define whether someone can use what you designed at all. A button that looks beautiful but cannot be reached by a keyboard is not a slightly flawed button. It is a broken one.

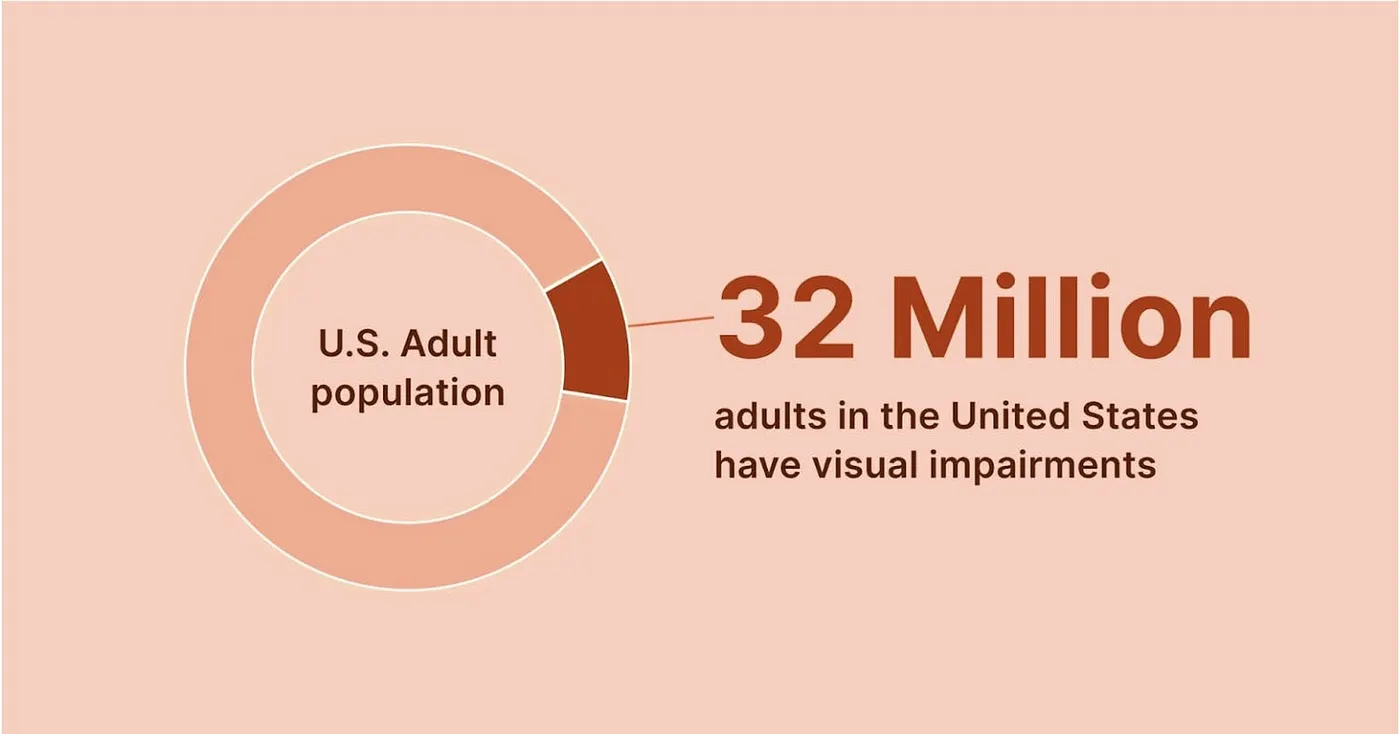

A common misconception is that accessibility is about designing for a small minority. In actuality, it is about designing for the real world.

Taking the figure above, 32 million adults in the United States having visual impairments, that's just shy of 12% of the entire adult population of the country. That's very much a not insignificant amount.

People use products in bright sunlight. With one hand. With aging eyes. With temporary injuries. With slow connections. With screen readers. With cognitive load. Accessibility covers permanent, temporary, and situational limitations. At some point, it covers all of us.

When accessibility is considered early, it rarely compromises aesthetics. Clear hierarchy improves scanability. Sufficient contrast improves legibility. Predictable interactions reduce cognitive effort. These things make designs better for everyone, not worse.

The real cost appears when accessibility is ignored. Retrofits are expensive. Engineering work increases. Design intent gets compromised. What could have been a simple decision becomes a negotiation.

As a designer, you are often the first person to decide who a product is for. Every choice you make either widens or narrows that circle. Accessibility is how you keep it open.

So future designer, do not ask whether something is accessible enough. Ask whether accessibility was part of the decision in the first place. Design as if everyone belongs there, because they do.

Further Reading

- The Designer's Guide to Web Accessibility on Smashing Magazine

- Designing for Web Accessibility on W3C Web Accessibility Initiative